Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4

50 Years of Opportunity and Innovation

The History of College of the Canyons

By John Green

Managing Director, District Communications

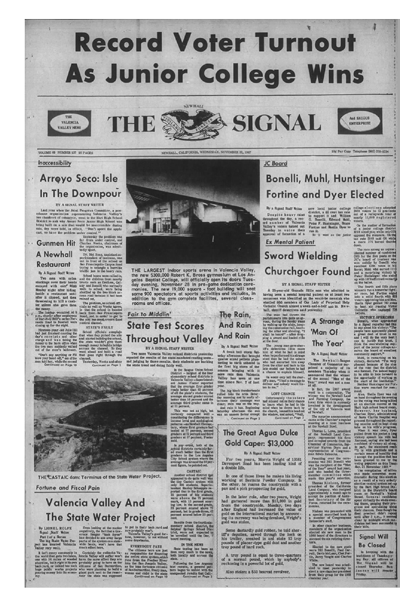

The first classes at College of the Canyons began in 1969, but this story actually begins two years earlier. That’s when the citizens of the Santa Clarita Valley decided it was time they had a college to call their own. On Nov. 21, 1967, they voted overwhelmingly to transform the idea into reality. While they were at it, they also elected a five-member board of trustees to oversee the creation of their new junior college.

Optimism abounded for what lay ahead. This once-sleepy whistle-stop along Southern

Pacific Railroad’s Los Angeles-to-San Francisco line was growing like it never had

before. In communities we now call Saugus and Canyon Country, a growing assortment

of tract homes was sprouting – although vast expanses of vacant or agricultural land

still separated the valley’s distinct communities. Downtown Newhall was the established

commercial center with car dealerships, a supermarket, a bank and other merchants

typical of a small town of fewer than 60,000 people.

Optimism abounded for what lay ahead. This once-sleepy whistle-stop along Southern

Pacific Railroad’s Los Angeles-to-San Francisco line was growing like it never had

before. In communities we now call Saugus and Canyon Country, a growing assortment

of tract homes was sprouting – although vast expanses of vacant or agricultural land

still separated the valley’s distinct communities. Downtown Newhall was the established

commercial center with car dealerships, a supermarket, a bank and other merchants

typical of a small town of fewer than 60,000 people.

But things were changing. And quickly.

During the summer of that pivotal year of 1967, the master-planned community of Valencia was born, luring young families from “over the hill” with homes priced at about $25,000. Valencia Town Center did not exist, of course. Neither did the Valencia Auto Mall. Magic Mountain, Henry Mayo Newhall Memorial Hospital and California Institute of the Arts were still several years from appearing on the local landscape. There was no Stevenson Ranch, just a vast unadulterated plain accented by rugged foothills, most of which have since been terraced and built upon. Old Orchard Shopping Center on Lyons Avenue and The Newhall Land & Farming Co.’s first golf course – Valencia Country Club – were barely two years old. The Valencia Industrial Center was just beginning to be developed. The single-screen Plaza Theater in Newhall and the Mustang Drive-In off Soledad Canyon Road were the lone cinematic venues.

The emergence of the Santa Clarita Valley as a viable place to live, work and play

was precipitated by several key developments, chief among them the country’s post-war

westward migration and California’s remarkable growth. The two greatest obstacles

to further development – limited access and insufficient water – were in the process

of being resolved. The old Highway 99 was steadily being circumvented by a major north/south

freeway, Interstate 5, that would cut a vital swath through the Santa Clarita Valley

on its way to becoming California’s most important roadway, connecting north with

south, border to border. And, following California voters’ approval seven years earlier

to bring state water south, plans were moving forward on a major new State Water Project

dam and reservoir in Castaic. This project, part of what would become the biggest

water-delivery system in the world, finally ensured a reliable source of water. All

of these developments set the stage for the dramatic transformation of a dusty domain

of cowboys and sodbusters into a rapidly growing suburbia, one that would need a public

institution of higher learning. Thus was born College of the Canyons, which would

go on to become one of the fastest-growing community colleges in California and the

nation.

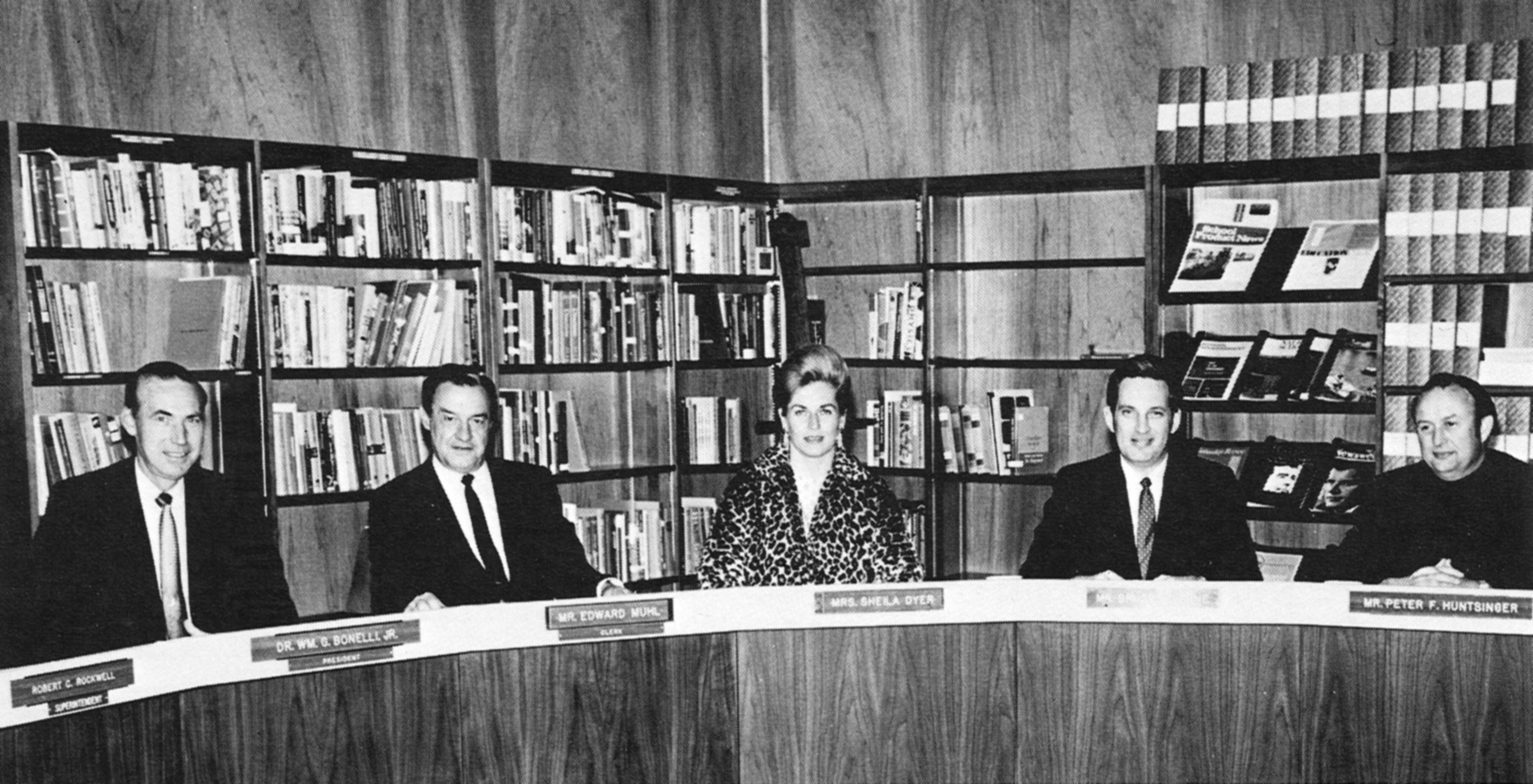

The first Board of Trustees (from left): President William Bonelli Jr., Vice President

Edward Muhl, and members Sheila Dyer, Bruce Fortine and Peter Huntsinger.

Getting Down to Business

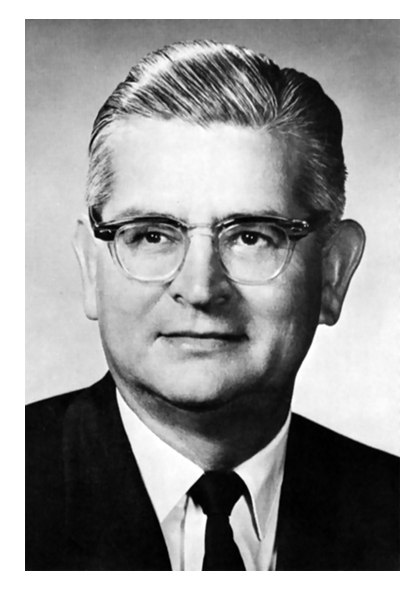

Things moved quickly once voters gave the go-ahead. The Board of Trustees – President

William Bonelli Jr., Vice President Edward Muhl, and members Peter Huntsinger, Sheila

Dyer and Bruce Fortine – began functioning as an official body on Dec. 5, 1967. They

initiated a search for someone who could create a college from the ground up and get

it running quickly. Santa Barbara City College President Dr. Robert C. Rockwell (pictured

at right) emerged as the top choice. He became the first superintendent of the Santa

Clarita Valley Junior College District, as it was then called, and the first president

of its college, which would eventually adopt the now-familiar name of College of the

Canyons.

Things moved quickly once voters gave the go-ahead. The Board of Trustees – President

William Bonelli Jr., Vice President Edward Muhl, and members Peter Huntsinger, Sheila

Dyer and Bruce Fortine – began functioning as an official body on Dec. 5, 1967. They

initiated a search for someone who could create a college from the ground up and get

it running quickly. Santa Barbara City College President Dr. Robert C. Rockwell (pictured

at right) emerged as the top choice. He became the first superintendent of the Santa

Clarita Valley Junior College District, as it was then called, and the first president

of its college, which would eventually adopt the now-familiar name of College of the

Canyons.

Other names were considered for the new college district, among them North Valley, Upper Santa Clarita Valley, Bouquet, Canyon, and Vasquez.

Asked why he would consider leaving a plush coastal clime for a dusty semi-desert outpost, Rockwell replied: “A college president has very few opportunities to create an entirely new college, and I’m still young enough to do it – and I want very much to do it.” The trustees liked his answer, as well as the fact he’d earlier overseen the construction of Cerritos Community College. Accompanying Rockwell from Santa Barbara was his loyal vice president, Gary Mouck, who would stay on at College of the Canyons long after his mentor retired. “College of the Canyons is what it is today because Bob Rockwell was the right man at the right place at the right time,” Mouck said. “There is simply no question about that. He brought invaluable experience and an innate leadership quality to the project.”

Rockwell, Mouck and the trustees soon began the crucial task of finding the people

who would give life and character to the new college. First to be built was an administrative

staff, composed of Charles Rheinschmidt, assistant superintendent-student personnel;

Carl McConnell, dean of admissions and records, and Joleen Block, director of library

services.

First Faculty Hired

Rockwell often boasted that he had personally “hand-picked” the college’s instructors. But they first had to get past Mouck, who interviewed and screened every one of them. During the months leading up to the first classes in the fall of 1969, he and fellow administrators turned their attention to recruiting the first faculty members. They sifted through the resumes of some 4,000 applicants. Thirty-one would be chosen.

The inaugural faculty were William Baker, communications; James Boykin, biological sciences; Louis Brown, police science; Steven Cerra, history; Theodore Collier, political science and history; Robert Downs, music; Alice Freeman (Betty Spilker), English; Kurt Freeman, psychology; George Guernsey, technology; Mildred Guernsey, mathematics; Ann Heidt, art and English; Donald Heidt, English; Donald Hellrigel, foreign language; Elfi Hummel, foreign language and drama; Leonard Herendeen, police science; Iris Ingham, art; Jack Israel, physical education; Edward Jacoby, physical education; Jan Keller, librarian; Thomas Lawrence Jr., physics; Clifford Layton, business and mathematics; Betty Lid, English; J.J. O’Brien, police science; George Pederson, police science; Lynora Saunders, physical education; Lee Smelser, physical education; Dale Smith, sociology and anthropology; Gretchen Thomson, history; Gary Valentine, chemistry and biology; Frances Wakefield, counseling, and Stanley Weikert, business.

The composition of the original Board of Trustees elected in 1967 changed, as John Hackney replaced Sheila Dyer in 1969.

The challenges facing the young district were formidable. Even with the key people

in place, the college still existed in concept only. There was nothing yet tangible

and very little money. By May 1969 the college’s first catalog was ready to go – minus

an important detail. “There was no cover because the college didn’t have a name,”

Mouck recalled years later. That issue would soon be resolved.

College Gets a Name

Mouck was in his office one day in early 1969, examining topographic maps of the Santa Clarita Valley, when he noticed the number of canyons. “I counted over 50. So I yelled out, ‘How about College of the Canyons?’ ” There already was a College of the Desert and a College of the Redwoods, so College of the Canyons made sense, he reasoned. On May 15, 1969, the Board of Trustees agreed. “College of the Canyons” won out over other suggestions such as Santa Clarita College and Valencia College.

The rationale behind the selection of the cougar as official mascot was far less complicated. “I came up with ’cougar’ because I like cougars,” Mouck said matter-of-factly.

Attention soon turned to the reason Mouck was examining topographic maps in the first place. The college needed a home. Although there were still vast swaths of vacant land in 1969, a significant portion of it was owned by one company, Newhall Land. The college identified some 45 possible properties on which to build, including land that Newhall Land and Sea World planned to transform into a major theme park. That place would open on May 29, 1971 as Magic Mountain and quickly become a regional landmark, but only after Newhall Land made college leaders an offer that was hard to pass up.

The company offered to sell the district more than 150 prime acres along Interstate

5 near Valencia Boulevard for about $10,000 an acre, then return 10 percent of the

purchase price as a gift. Now, all the district needed was the money.

The college's first classes began at Hart High School on Sept. 29, 1969.

Classes Begin

With hundreds of prospective students eagerly awaiting their new college, temporary quarters were arranged at Hart High School. It was there, in a Newhall Avenue bungalow, that College of the Canyons officially welcome its first class of students on Monday, Sept. 29, 1969. Rockwell expected about 600 people to sign up for that first fall quarter. But, in a precursor to the years that would follow, demand was underestimated as 735 students showed up.

Administrative offices were located several blocks away, at 24609 Arch Street, in a strip-mall storefront just over the railroad tracks at San Fernando Road (now called Main Street). The college organized its first-year schedule around the quarter system, with the winter quarter starting Jan. 7, 1970 and the spring quarter commencing April 8, 1970. There was no summer session.

Courses of instruction were comprehensive for such a new institution. More than 150 classes were offered in anthropology, art, astronomy, automotive technology, biological sciences, business, chemistry, communications, economics, engineering, English, French, geography, geology, German, health education, history, home economics, library technology, mathematics, meteorology, music, philosophy, physical education, physics, police science, political science, psychology, social science, sociology and Spanish.

The college fielded its first athletic teams in baseball, basketball, cross country and track under the auspices of the Desert Conference.

Student activities began immediately. The college’s first student body president,

Paul Driver, was elected. The first issue of the student newspaper, “The College Sound,”

rolled off the press in November. A steady succession of events with names such as

Sweethearts Dance and Annual Awards Banquet followed, as did theatrical productions

such as “The World of Ferlinghetti” and “Our Town.”

First Commencement

Before long, the college’s first commencement day arrived. Assembled in the Hart High cafeteria on June 26, 1970 were Dennis Agajanian – the first to be handed his diploma – Karen Bright, Karen Coe, Penny Curtis, John Dalby, Richard Dalmage, Loren Elmore, Stuart Harte, Rita Hendrixson, Gregory Jenkins, Andrew Kress, Georgia Lucas, Emily Sifferman, Shirley Stein, Robert Wilder and Wayne Williams. These 16 people hold the distinction of being the very first graduates of College of the Canyons.

“The first year of operation of any new college is never easy,” Rockwell remarked during the ceremony. “The challenges are numerous. All of you have met these challenges and, in doing so, have achieved an enviable place in the history of this college.”

The Hart High campus filled an urgent need, but it was ill-suited to accommodate a growing college for very long. Instructional hours were restricted because classes could begin only in the late afternoon, after high school students had left for the day. Before the year was out, College of the Canyons would have a new home.

In January of 1970, voters gave their resounding approval to a $4 million construction-bond issue so that College of the Canyons could create a permanent campus. The district took Newhall Land up on its earlier offer and purchased 153.4 acres of land bounded by Valencia Boulevard on the north and Interstate 5 on the west. “Ultimately we obtained the best site of all,” Mouck said, referring to the gently rolling oak-studded hills along the east side of Interstate 5.

College of the Canyons moved out of Hart High in July, setting up a temporary admissions

office in a garage on Pine Street until the new campus was ready.

The first campus at the college's permanent home opened in 1970 and consisted of modular

buildings housing 99 classrooms.

A Permanent Home

Just 10 months after the bond issue’s passage, portable buildings housing 99 classrooms were erected on the Valencia Boulevard property. Classes began here on the site of the present-day softball field on Oct. 5, 1970, two weeks later than planned because delivery of the portables was delayed. Faculty, staff and students would alternately call the assemblage of prefabricated buildings the “Instant Campus” or “Stalag 13,” the latter a reference to the bleak prisoner-of-war camp in the TV sitcom “Hogan’s Heroes.”

“When the temporary buildings finally arrived, they were placed somewhat in a circle, with the library situated in the middle of the complex – a design that always reminded me of a wagon train rounded up to fight off the Indians, but in our case just some rather ‘rough around the edges’ kids off the local farms and ranches,” said Roger Basham, who was hired to teach anthropology in 1970.

Once the portable buildings were in place, work commenced on the adjacent football field and surrounding all-weather Tartan Track for track and field competition. The massive concrete stadium and lights would come later, after the visitors’ stands were built.

At the start of the second academic year, the student body was more than 1,200 strong, a compelling indicator of community need and the growth yet to come.

The budding student body was now offered more than 225 courses taught by an ever-growing faculty team. New instructors included Basham, anthropology; Marcia Boehm; Carl Buckel, management; Janice Burbank, nursing education; Dorothy Burtch; Doris Coy, business and economics; Barbara Hamm; Willard Kiesner; Roseann Krane; Chris Mathison; Robert McNutt; Stanley Newcomb; Ken Palmer; Anton Remenih, communication services; Robert Seippel; Carl Seltzer; William Solberg, and Winston Wutkee, geology. And, although the name was new, the face was familiar, as Alice Freeman rejoined the faculty ranks under her new, married name, Betty Spilker. Joining the administrative team in 1970 were Robert Berson, assistant superintendent-business services, and Al Adelini, dean of student activities.

The name of the district was shortened slightly, with the removal of “Valley” from

the Santa Clarita Valley Junior College District. (In fact, the official district

name would change again when California decided to rename its junior colleges “community

colleges.” The Santa Clarita Community College District became official in 1972.)

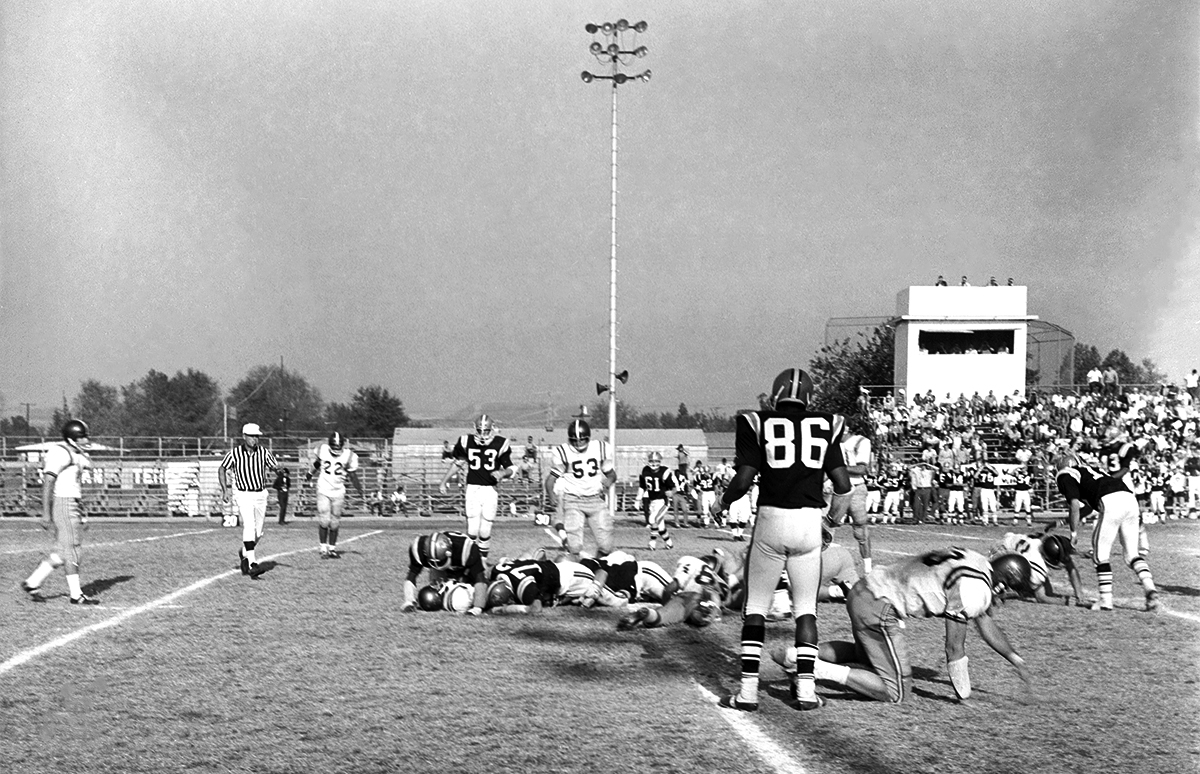

The football team plays Victor Valley College at Hart High School in 1970.

Athletic Teams Excel

Putting the new football field to good use was the college’s first gridiron squad, which announced its arrival by winning the season opener against the Cal Lutheran junior varsity team by a score of 49-6. The 1970 Cougars, coached by Don Kloppenburg, finished the season with a 7-2 record, second in the Desert Conference and fifth in the state. The first-year team also produced an All-American in tailback Clint McKinney, who gained the most yardage – 413 in 41 carries – in a single game in the history of American college football. McKinney was named MVP of the Desert Conference and presented with a special trophy from Sports Illustrated magazine.

The cross-country team, headed by coach Ed Jacoby, won the conference championship. The harriers’ captain and star was Mike Martinez.

The college’s Alma Mater, authored by music instructor Robert Downs, appeared for the first time in the 1970-71 Cougars Handbook: “All hail to Thee with melody, our voices strong and clear. We pledge to Thee our loyalty in terms for all to hear. And when we go our way, we will say we have known you, Alma Mater, strong and true. Our College of the Canyons and a Cougars’ victory! All hail to Thee.”

Students held their first welcome dance of the new academic year at Hart High, whose multi-purpose room was still larger than anything at the new campus. Performing on stage was a band with the unusual name of “Shmoogi,” whose roster included a young Curtis Stone. Son of the late music legend and Saugus resident Cliffie Stone, Curtis would later find stardom as a founding member of the country band “Highway 101.”

Meanwhile, the once-virgin hills were being reshaped by dozens of clattering steel

behemoths that kicked up an endless supply of dirt and dust in their quest to create

a habitable college campus. The street address for the college was 25000 Valencia

Boulevard, as Rockwell Canyon Road did not yet exist.

Meanwhile, the once-virgin hills were being reshaped by dozens of clattering steel

behemoths that kicked up an endless supply of dirt and dust in their quest to create

a habitable college campus. The street address for the college was 25000 Valencia

Boulevard, as Rockwell Canyon Road did not yet exist.

Unlike the present-day campus, the new college had a serious parking problem. Consequently, it was common to see hundreds of cars parked bumper-to-bumper along both sides of Valencia Boulevard when classes were in session.

Improvisation was the order of the day. Students could occasionally be seen hosing down the inevitable layer of dirt and grime that accumulated on just about everything, while instructors often abandoned the confines of the prefabs to teach outdoors. Basketball coach Lee Smelser once conducted a class while perched atop the back of a pickup truck, and English instructor Betty Lid transformed a trash can into a speaking lectern.

“Classes were often taught outside of the portable buildings, as they were poorly

ventilated and the A/C units made a terrible racket, so we simply picked up our chairs

and went outside to conduct classes,” Basham recalled. “Curtains separated the two

classes sharing the same portable building, so students sitting in the back of the

classrooms could listen to two lectures at the same time. When a film was shown, it

didn’t matter which classroom one was sitting in. Everyone heard it.”

Sen. George Murphy (left) and Bob Hope sign autographs for cheerleaders during the

Oct. 26, 1970 dedication of the College of the Canyons campus.

Stars Come Out

On Oct. 26, 1970, during a twilight ceremony under a mammoth green-and-white tent, College of the Canyons was officially dedicated. More than 700 people showed up to witness the hour-long event in the center of the campus. Special guest speakers were comedian Bob Hope and U.S. Sen. George Murphy.

“The pioneer spirit of the West is still here,” said Murphy, whose previous career as an actor featured roles on Broadway and in some 55 movies. “Nowhere have I witnessed a modern-day demonstration of our great pioneer spirit that surpasses the one taking place right here on this campus.”

When it was his turn to speak, Hope, the legend of standup comedy and the silver screen, took a swipe at campus radicals, reflecting the university unrest typical of the day. “I can’t understand how people can burn down college buildings,” he said. “For fine young students to be denied an education by a lousy fringe group is the biggest crime in our history.”

He also added his lighthearted take on the event. Referring to the tent in which everyone was assembled, Hope quipped: “I haven’t worked anything like this since Ringling Bros.” After taking in a deep breath, he added: “I’m in shock. This fresh air grabbed me. I’m not used to it. I’m from Burbank.”

“Our goal is not to provide just a college for the community, but a college of quality,

one that will be admired and used as a model throughout the state,” Rockwell said

to the assembled guests. “With our staff and administration, this goal is within our

grasp.”

Campus Gets a Jolt

The timing of the 6.4-magnitude Sylmar earthquake on Feb. 9, 1971 was fortuitous for College of the Canyons. No permanent campus structures yet existed, but the architectural plans for the buildings on the drawing board were beefed up significantly to make the college’s first structures among the safest in California.

“The Student Center was supposed to be two stories, but everything changed the day of the Sylmar earthquake,” said Adelini, dean of student activities. “That was a very fateful day for the college, and we became the most earthquake-ready facility in the whole valley.”

Hardest hit during the quake – which was strong enough to topple the lofty Interstate 5-Highway 14 interchange that was then under construction – was the library, where librarian Jan Keller estimated that some 10,000 volumes lay buried under displaced steel shelves. It took two days to sort through the mess and re-shelve the books.

Eighty-nine students graduated during the college’s second commencement ceremony – the first to occur on the permanent campus – in 1971. The figure was more than five times greater than the 16 graduates a year earlier and a portent of things to come.

By the fall of 1971, enrollment continued to experience dramatic growth, reaching 1,700 students – more than twice the number of students enrolled in classes during the first year. The number of college personnel also continued to grow to meet the increased enrollment demands. Hired to serve as dean of vocational-technical education in 1971 was Robert Pollock, and new faculty members included Hazel Carter, nursing education; Henry Endler, transportation; Robert Freeman, music; Helen Lusk, nursing education, and Larry Reisbig, physical education.

The college’s new vocational nursing program awarded 11 students with nursing caps in April 1971. The mid-year “capping” ceremony marked the halfway point for the students, who were enrolled in an intensive training program that included more than 1,000 hours of clinical training at Inter-Valley Community Hospital in Saugus and Golden State Memorial Hospital in Newhall. “You are preparing yourselves for a noble calling,” Assistant Superintendent Mouck told the students. The class later graduated in August.

Meanwhile, a wayfaring pair of geology and anthropology instructors began conducting field trips that would become institutional traditions – and wildly popular among students. Geology instructor Winston Wutkee, a strong believer in hands-on rock hunting, led several field trips to places such as Acton, Tick Canyon, Death Valley and Gold Rush country, where students could find and inspect actual specimens on their own. Likewise, anthropology instructor Basham led expeditions in which students participated in archeological digs. Among the destinations was a site near the then-new Castaic Dam to unearth evidence of a Chumash tribe that once inhabited the area. Another focused on a dry lake bed near Taft, where students dug up arrowheads, beads and other artifacts left behind by the Yokuts, who occupied the San Joaquin Valley for some 7,000 years.

The college debuted its new marching band and crowned its first homecoming queen – Vicki Sinclair – during half-time ceremonies in November. The mighty Cougar football squad dispensed the College of the Desert Roadrunners by the score of 49-0. The 25-piece band was assembled by music instructor Robert Downs.

As 1972 began, it was impossible to ignore the small mechanized army of bulldozers and graders that was reshaping the property south of the temporary campus. The $1 million project was preparing the land for the buildings that would eventually rise from the site, including the first permanent building, the Instructional Resource Center (now called Bonelli Hall), as well as the Classroom Center (Seco Hall), Laboratory Center (Boykin Hall), Student Center, Vocational-Technical Building (Towsley Hall) and portions of the Physical Education Center.

Dr. William Bonelli, the recently re-elected first president of the Board of Trustees, did not live to see the college’s first permanent building. He died suddenly on Feb. 22, 1972 at the age of 49. The college’s first permanent structure, the Instructional Resource Center (IRC), would be renamed in his honor. Newhall’s postmaster, Francis Claffey, was elected to fill the vacant board seat.

The second commencement ceremony on the permanent campus produced 143 graduates –

up from 89 the previous year. The college was experiencing solid growth, but even

that was dwarfed by bigger news: Construction of the Dr. William G. Bonelli Instructional

Resource Center was authorized to move forward.

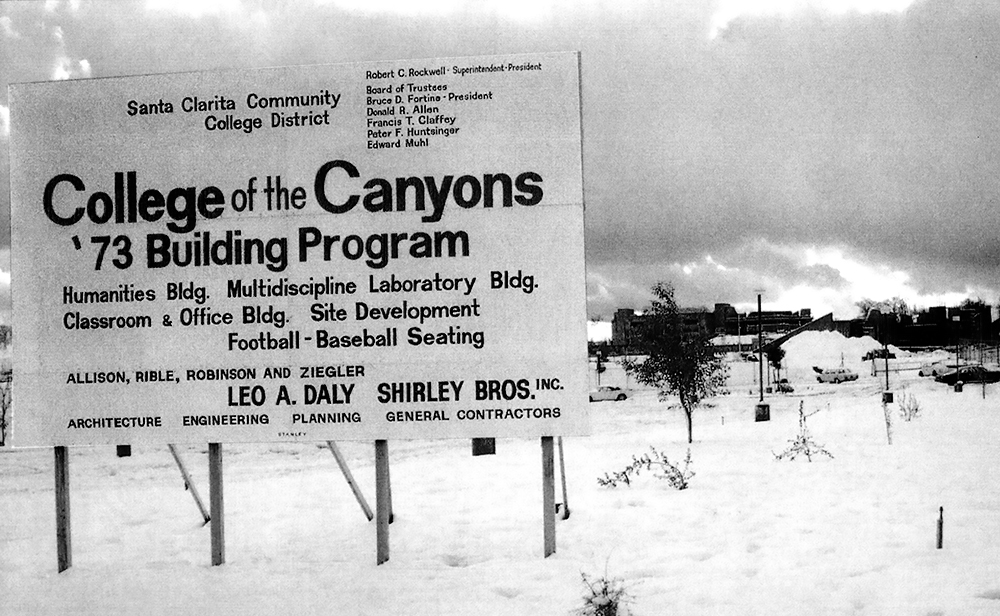

A sign announces the building program for the new Valencia campus, which is blanketed

in snow.

Community Rallies

In November 1972, voters statewide authorized the $160 million Community College Construction Act, which was worth about $11.2 million for College of the Canyons – provided that local citizens came up with at least $2.5 million in matching funds.

The challenge galvanized the community. Elisha Agajanian, board chairman of Santa Clarita National Bank, and Blake V. Blakey, manager of Anawalt Lumber & Materials Co., headed a group of some 40 community leaders who organized the Citizens’ Committee to Complete College of the Canyons. The outcome was extraordinary. On Feb. 6, 1973, local voters threw their support behind an $8 million bond issue to meet the matching-funds requirement of the earlier statewide measure. In fact, nearly 80 percent of the local electorate voted to support the measure, far surpassing the required two-thirds majority.

Construction of the IRC and an auto shop building was already under way. With the funding now in place, the core campus – most of it, anyway – could now be completed. Buildings began opening in rapid succession, with the monikers “Instant Campus” and “Stalag 13” fading into history.

The bond funding paved the way for five major building projects: the Laboratory Center (Boykin Hall), Classroom Center (Seco Hall), Student Center, Vocational-Technical Building (Towsley Hall) and Physical Education Center. The original master plan also called for a Theatre Arts Building, Music Building, Business Education Building and Classroom-Administration Building, all of which were scheduled to be built later in the decade.

Ultimately, the college envisioned under the first master plan would be able to accommodate

5,000 students – a capacity that would be met and surpassed far sooner than anyone

expected.

Gov. Ronald Reagan speaks during a dedication ceremony for the college's first building,

the Instruction Resource Center (now known as Bonelli Hall), on April 22, 1974.

First Buildings Completed

The first permanent building to be completed was the IRC (now called Bonelli Hall). More than half a million cubic yards of earth were moved to make way for this first building, which cost $3.25 million to build and housed 26 classrooms and faculty offices. As the IRC was completed and its classroom space made available in early 1974, the modular structures that had served as the college campus were abandoned and removed. At the same time, five other buildings were in various stages of construction.

The IRC was officially dedicated by Gov. Ronald Reagan on April 22, 1974. The dedication ceremony was a proud and lavish affair, with a large stage erected on the football field to accommodate the governor and other luminaries. Reagan arrived by limousine and met privately with college officials in the old board room, located inside a modular building behind where the present-day stadium scoreboard sits. Hundreds gathered in the field’s visitors’ stands as armed, mounted police officers patrolled the nearby hillside.

As the fall of 1974 approached, it was becoming abundantly clear that College of the Canyons had a vital purpose and an ever-expanding following. As the college entered its sixth academic year, enrollment rose to 2,542 students.

It was a time when many young people were returning from combat in Vietnam. Enrollment reflected this trend, with veterans accounting for a full 30 percent of the student population. The conflict in Vietnam would officially cease the following year.

The 6,000-seat Cougar Stadium officially opened for the football team’s first home

game of the 1974 season on Sept. 21 of that year. Unfortunately, the Cougars fell

to Los Angeles Harbor Community College by a score of 26-21.

The Classroom Building (now called Seco Hall) is under construction in the foreground,

while work continues on the Laboratory Building (Boykin Hall) in the background.

The Classroom Center (now called Seco Hall) and Laboratory Center (now Boykin Hall), two separate structures that were built on either end of the IRC, opened in January 1975. The scaled-back Student Center, now relegated to a single story in the interest of earthquake safety, opened in February 1975. The first on-campus dining facility opened here in September, offering a hamburger for 60 cents, a grilled-cheese sandwich for 40 cents and a large Coke for 35 cents.

The $1.2 million Vocational-Technical Building (now called Towsley Hall), housing programs in welding, automotive repair and home economics, opened to some 500 students in the fall of 1975. And, the nearly $5 million Physical Education Complex, housing an indoor swimming and diving pool, basketball court, gymnastics room and weight-training room, opened in March 1976. It signaled the end of construction of the original core campus. The Santa Clarita Valley now boasted a stunning college campus that was the envy of many a community.

“The modern architecture utilizes the natural landscape, reflecting in its design the spaciousness and simplicity of the terrain,” noted a college brochure from 1975, explaining the design philosophy of the new campus. “While certain changes in the hillsides must be made to complete the program, every effort has been made to ensure ecological protection.”

The sturdy, massive poured-concrete structures were designed to withstand 100-year

earthquakes and went well beyond state safety laws. “I doubt that we could afford

to build like that today,” Rockwell commented some years later. “I guess what the

founding Board of Trustees and I are proudest of is the fact that we planned well

for the future. It’s paying off handsomely now and will for decades to come.”

Dr. Robert Rockwell speaks during an event at the original modular campus.

Rockwell served College of the Canyons for more than a decade, retiring in late 1978

and accomplishing what the first Board of Trustees asked him to do: Build not just

a college, but a foundation on which to build. “I am proud of College of the Canyons,”

he said. “I consider it the culmination of a career.” Mouck was tapped to serve as

interim superintendent-president, a position he held until midway through the following

year.

Financial Challenges

The year 1978 was a transitional one for the college, if not the entire state. In November, California voters approved Proposition 13, a far-reaching measure that would have a profound impact on state finances and prompt cutbacks in educational programs. The dawn of this new era at College of the Canyons would be overseen by Dr. Leland B. Newcomer, former president of La Verne College, who was brought on board to replace the retiring Rockwell. Newcomer began his new job on July 1, 1979.

The financial challenges of the new decade would require innovative solutions. Faced

with a 10 percent increase in enrollment and a $500,000 deficit at the start of the

1980-81 academic year, the college embarked on a new course of action. It created

the College of the Canyons Foundation, a private, non-profit corporation that would

generate new funding from within the community to help fund educational programs and

provide scholarships, fellowships and grants for students.

Cougar pitching standout Bob Walk went straight to the Big Leagues in 1980, achieving

11 regular-season wins and a victory in Game 1 of the World Series for the Philadelphia

Phillies.

A welcome diversion would come from the sports world. Cougar pitching standout Bob

Walk broke into the big leagues and began playing for the Philadelphia Phillies on

May 26, 1980. Although not the first Cougar to make it to the pros, Walk was the first

to make a significant impact in professional sports. The fierce competitor’s 1980

rookie season at Philadelphia included 11 regular-season wins and a victory in Game

1 of the World Series. His phenomenal Major League Baseball career would stretch through

the ’80s, coming to a close with the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1993.

Deficits and Cutbacks

Despite a poor economic climate, construction began in January 1981 on a new Child Development Center and Administration Building, financed through the sale of bonds that were approved years earlier. Elsewhere on campus, college officials were struggling with the economic realities of the post-Proposition 13 climate.

A second-straight deficit, this one in the $600,000 range, resulted in a variety of cutbacks in the 1981-82 academic year. Scaled back or eliminated were music and theater programs, counseling services and speech classes. Although the situation appeared dire, Newcomer remained optimistic, commenting: “This college will survive. We can and will grow.”

The College Services Building, housing the Child Development Center (CDC) and administrative offices, opened its doors in February 1982. The CDC served the dual role of training students and providing preschool services to the community. The exceptional quality of care quickly became evident to local families, with lengthy waiting lists becoming the norm.

The year 1982 was a pivotal one for college athletics. Although the football program was successful on the field, it failed to capture the hearts and minds of the community. Mired in controversy over its recruitment of out-of-state players, the football program was dismantled at the order of the Board of Trustees, which rationalized its decision by pointing to the program’s high costs and the community’s apparent lack of interest. Lest anyone think it singled out football, the board also eliminated one-third of the physical education classes and a host of academic programs.

This year marks College of the Canyons’ 50th anniversary of serving the Santa Clarita

Valley.

This year marks College of the Canyons’ 50th anniversary of serving the Santa Clarita

Valley.